In a candlelit study just outside of Bologna in 1665, the Italian physician Marcello Malpighi set about trying to uncover the mystery of touch. He started off by dissecting a cow’s tongue, and what he found laid the foundations for the physiology of taste — how we make sense of why things are delicious, less delicious and downright disgusting. Then he moved onto the second item, a pig’s hoof. After removing the trotter from the gurgling soup, Malpighi grabbed a scalpel, then a set of tweezers and peeled back the successive layers of tissue until he stumbled across a tiny membrane with pigment (what we now call melanin) seemingly suspended amidst a lattice of tiny filaments. He had seen something familiar during his human dissections and offhandedly suggested that this mucus little layer — which would henceforth be named the ‘rete Malpighi’ — determined the different skin colours of both pigs and people. What’s more, he observed that if he scraped just a little further down, this black, seemingly liquid substance gave way to a more neutral hue. "It is certain that the cutis (of the Ethiopian) is white, as is the cuticula too,” he wrote, going on to observe that “their blackness arises from the underlying mucous and netlike body.”

Malpighi died in 1694 and is famously referred to as the father of modern physiology and embryology, as well as the man who popularised microscopes. He was the first person to discover the link between arteries and veins, to observe capillaries in animals and the second to observe red blood cells. What people talk about less is Malpighi was also the guy who made the idea of ‘race’ as a scientific category possible.

He couldn’t have known it at the time but his observations about that hoof had effectively reduced human difference to a single physical feature that some people appeared to have and others didn’t. We’ve been dredging up the consequences ever since.

The Seat of Colour

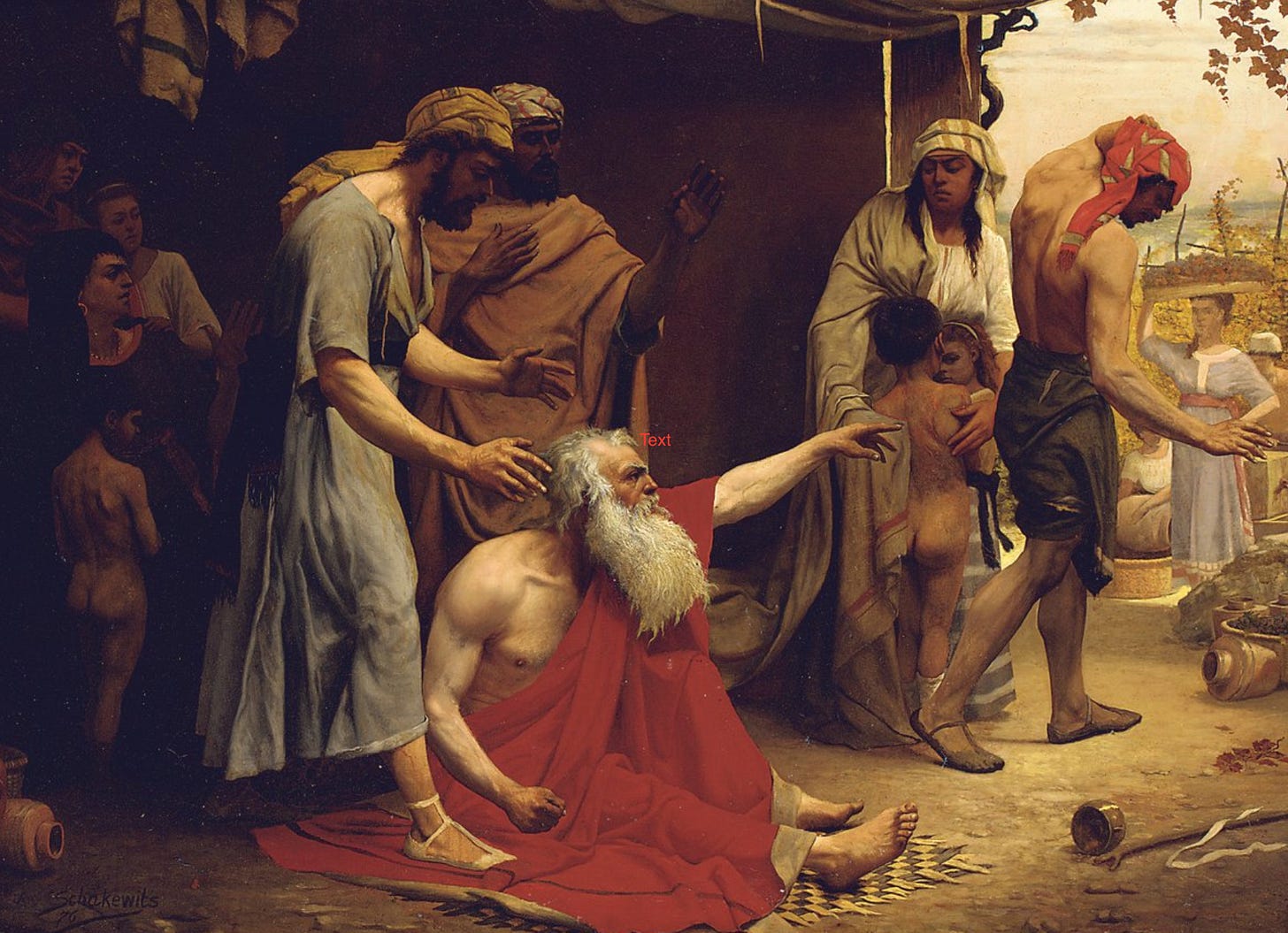

Explanations for why some humans had darker skin than others were nothing new, Hippocrates and many of his Greek and Roman successors reasoning it was all a response to bodily humours, sunlight and the surrounding environment. But with the spread of the Abrahamic religions, another theory increasingly took root called the Hamitic Curse. The story comes from Genesis and recounts how after Noah and his family went ashore to repopulate the world following the flood. One night he passed out in a drunken stupor without his clothes and his son Ham spotted him. In a fit of rage, Noah cursed his son, damning Ham and his progeny to perpetual servitude.

The story ends there in the book of Genesis but given it’s implications (that we’re all descended from Noah’s nearest and dearest), subsequent thinkers from Jewish, Muslim and Christian traditions interpreted the account as both an explanation for dark-skinned Africans as well as a means of justifying their enslavement.

Perilously suspended atop this distinction was another debate that emerged following the ‘discovery’ of the Americas: those who argued human beings of all different stripes were one and the same species and those who argued they weren’t. Today, we call those opposing camps monogenism and polygenism. And while Malpighi didn’t mention either, he had unwittingly furnished exponents of both with what appeared to be the missing piece of the jig-saw. Before him, skin pigmentation, the observable phenotype often used as a shorthand for ‘race’ was largely an exterior question, determined either by the weather or the whims of the almighty. After him, it became an interior one. Not only was the answer seemingly nestled between filaments and cuticles of flesh, people thought it had something to do with black pigment superimposed on a reassuringly pristine, white canvas.